Life Is So Short

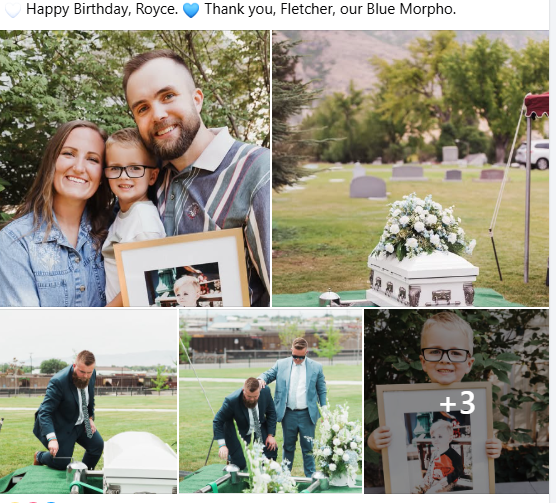

Yesterday marked what would have been Royce’s ninth birthday. Every year, as that day comes around, the air feels heavier and the world moves a little slower. Time doesn’t heal all wounds—it only teaches us how to carry them differently. And this year, something changed. Our younger son, Fletcher, now old enough to understand that his family has a missing piece, began asking questions that cut deeper than I ever expected.

We spent the day remembering Royce in our favorite way—through color, love, and quiet reflection. We painted pumpkins, each one bursting with shades of orange and white, the way Royce used to love when he was little. Then we carried them to his headstone, a ritual we’ve repeated year after year. The cemetery was calm, the autumn breeze soft but cool. As we stood there, Fletcher began singing “Happy Birthday” before any of us could find our voices. His small, shaky tune broke something open inside me, and soon everyone joined in—our voices trembling, the words catching in our throats. The song was simple, but it carried a weight no melody should ever have to hold.

That night, after the candles had been blown out and the tears had dried, I lay next to Fletcher in bed. The room was dark, except for the faint glow of the nightlight, and I could tell his thoughts were far away.

“What are you thinking about, bud?” I asked softly.

He turned toward me, his voice barely above a whisper. “Where was Royce for his birthday party?”

It was such an innocent question, one filled with pure curiosity—but it pierced through me like a knife. In that moment, I realized he still didn’t fully understand what it meant for his brother to be gone. So I tried to explain, carefully, gently—that Royce had passed on, that his body rests beneath the headstone where we sang that morning.

That explanation, of course, only led to more questions. “How did he get put there?” Fletcher asked, his brow furrowed in that way he does when he’s trying to understand something big.

It’s impossible to prepare for a conversation like that. Memories I’d kept buried came flooding back—the funeral, the stillness, the weight of goodbye. Before Royce’s funeral, the mortuary had asked if we had any special requests. I had only one. I wanted to lower my son into the ground myself.

During my time in New Zealand, I had learned from the Māori people that lowering a loved one’s body is a sacred act—a final expression of care. It means you will carry them all the way home, that your love doesn’t stop where life does. That belief stayed with me. So when the time came, I did it for Royce. My hands trembled as I held the rope, the reality of it pressing against my chest, but it felt like the only way I could keep that promise: I will carry you all the way home.

Someone took a photo during that moment. I hadn’t planned on ever showing it to anyone, but later, when Fletcher asked, I brought it out. I showed him so he could understand—that Royce had been in a coffin, that I was the one who placed him beneath the earth, connecting what we say about heaven with something he could see and touch.

We often tell Fletcher that Royce is a white butterfly, the kind that drifts through our yard when the sun is low. It brings him comfort to think his brother is nearby, fluttering softly, free from pain. That night, after I showed him the picture, Fletcher looked up and said quietly, “Then I want to be a Blue Morpho when I become a butterfly.”

I smiled through tears. “You won’t be a butterfly for a long, long time,” I told him. “Mommy and I will be butterflies first.”

He looked at me with that same mix of innocence and wisdom children somehow carry. “When you become a butterfly,” he asked, “will you make sure to find me?”

That question broke me open. All the ache of the day—the birthday songs, the memories, the missing—rushed to the surface. I called Lindsie into the room, unable to hold it in any longer. She lay down beside him, wrapping her arms around us both.

And then, in that soft, sleepy voice, Fletcher said something I will never forget. “Mom,” he whispered, “I’ll lower you and Dad into the ground, okay?”

We both completely lost it. Tears came uncontrollably, the kind that come from a place too deep for words. There, in the quiet of his room, surrounded by innocence and love, we felt everything all at once—grief, gratitude, and the unspoken truth that life is unbearably short.

That night, long after Fletcher had fallen asleep, I lay awake thinking about those words. About how children see death not as an end, but as a continuation of love. How their hearts can hold both sorrow and wonder in the same breath.

I thought about how easily we let days slip by, assuming there will always be another chance to say “I love you,” another moment to listen, to hold, to see. But the truth is, we never know how many days we have. One morning, you’re painting pumpkins for a birthday; the next, you’re clinging to memories and photos to feel close to someone you can’t touch anymore.

What Fletcher gave me that day was a reminder—a painfully beautiful one—that we shouldn’t wait until our loved ones become butterflies to truly see them. We need to hold them, cherish them, and tell them how deeply we love them while they are still here, breathing the same air, laughing at the same table, singing the same song.

I hope Fletcher always stays curious about his brother. I hope he never stops asking questions, never stops feeling connected. Because in those questions lies something sacred—the bridge between life and what comes after.

And maybe, just maybe, when it’s our time to become butterflies, we’ll find each other again—drawn together by love, by memory, by the promise that even the shortest lives can leave the longest echoes.